The ‘Left to Die’ Boat Scandal: How Dozens of Migrants Were Left By NATO Military Units to Perish at Sea

An exclusive investigation for the Guardian that provoked international outrage, and forced a policy change across Europe

-Published in the Guardian

-Lampedusa, London, Brussels and Strasbourg / 2011-2012

-Winner of ‘News Story of the Year’ at the 2012 One World media awards

In the early hours of March 26th, 2011, under the cover of darkness, 72 men, women and children made their way down to a small inflatable dinghy on the shores of Tripoli and set sail for what they hoped would be a new life in Europe. Only nine people survived the journey.

In an exclusive investigation for the Guardian, Jack Shenker broke the story of what happened to the boat - and revealed that, after running into trouble, its occupants had made contact with a NATO warship and a European military helicopter at sea, only to find their cries for help ignored.

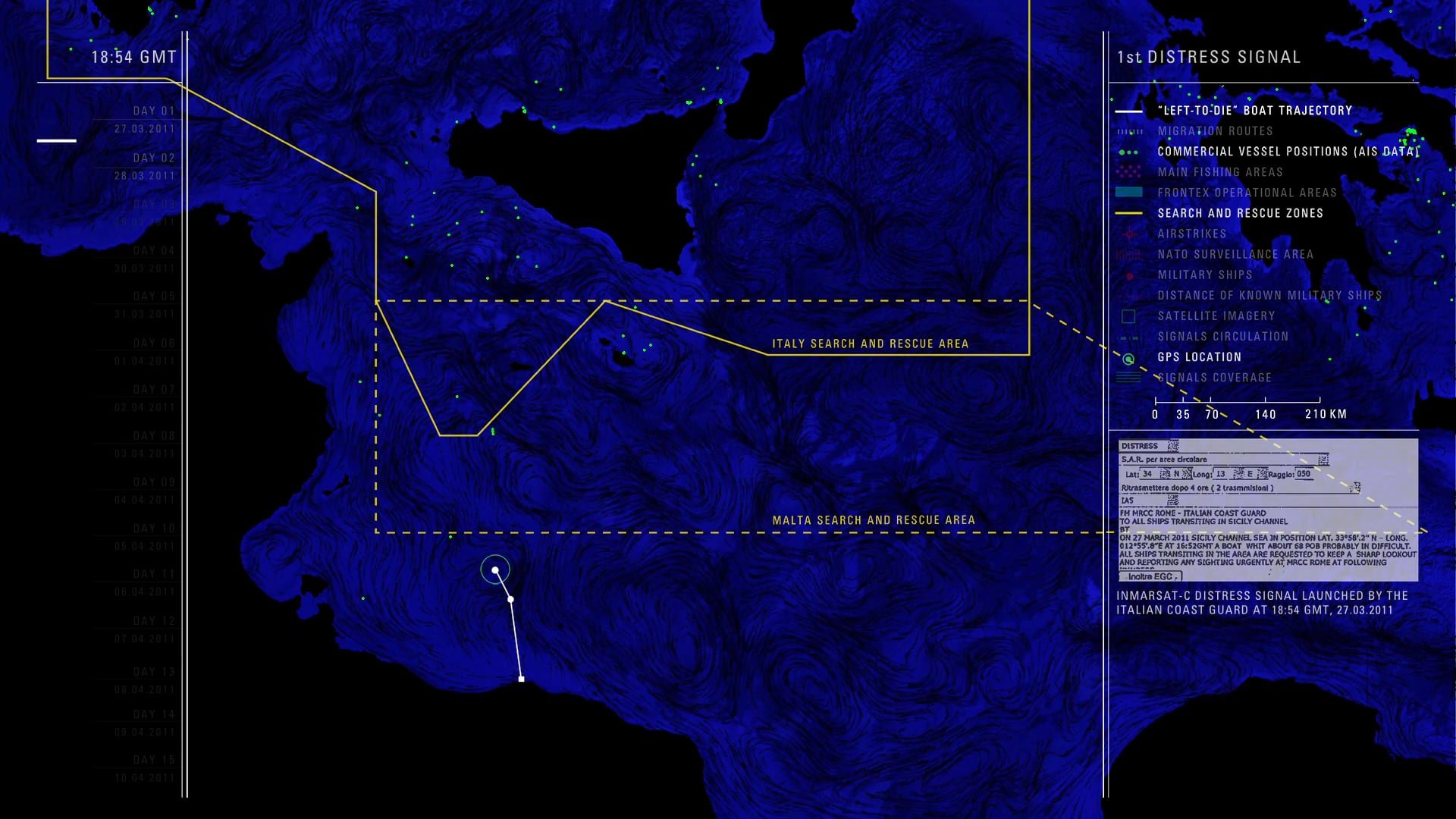

Across a series of news articles and features spanning nearly a year, the investigation pushed for accountability for the deaths and was widely covered in the global media. Two major reports into the scandal - conducted by the Forensic Architecture team, and the Council of Europe - were subsequently published, and as a result the continent’s leading human rights body adopted a new set of protocols regarding search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean. After initially denying any responsibility, NATO eventually expressed “deep regret” for its role in the tragedy.

Below is the original news story, followed by excerpts from and links to some of Jack’s many follow-up articles across the course of the investigation, some of which were co-written by colleagues in Italy, France and Spain. The Forensic Architecture report, which was later featured in exhibitions held at the National Maritime Museum and the ICA in London, is available to read here. The Council of Europe report, along with details of the subsequent resolutions passed by the organisation, is online here.

Aircraft carrier left us to die, say migrants

Exclusive: Boat trying to reach Lampedusa was left to drift in Mediterranean for 16 days, despite alarm being raised

8th May 2011 - read the full story here

Dozens of African migrants were left to die in the Mediterranean after a number of European military units apparently ignored their cries for help, the Guardian has learned. Two of the nine survivors claim this included a Nato ship.

A boat carrying 72 passengers, including several women, young children and political refugees, ran into trouble in late March after leaving Tripoli for the Italian island of Lampedusa. Despite alarms being raised with the Italian coastguard and the boat making contact with a military helicopter and a warship, no rescue effort was attempted.

All but 11 of those on board died from thirst and hunger after their vessel was left to drift in open waters for 16 days. "Every morning we would wake up and find more bodies, which we would leave for 24 hours and then throw overboard," said Abu Kurke, one of only nine survivors. "By the final days, we didn't know ourselves … everyone was either praying, or dying."

International maritime law compels all vessels, including military units, to answer distress calls from nearby boats and to offer help where possible. Refugee rights campaigners have demanded an investigation into the deaths, while the UNHCR, the UN's refugee agency, has called for stricter co-operation among commercial and military vessels in the Mediterranean in an effort to save human lives.

"The Mediterranean cannot become the wild west," said spokeswoman Laura Boldrini. "Those who do not rescue people at sea cannot remain unpunished."

Her words were echoed by Father Moses Zerai, an Eritrean priest in Rome who runs the refugee rights organisation Habeshia, and who was one of the last people to be in communication with the migrant boat before the battery in its satellite phone ran out.

"There was an abdication of responsibility which led to the deaths of over 60 people, including children," he claimed. "That constitutes a crime, and that crime cannot go unpunished just because the victims were African migrants and not tourists on a cruise liner."

This year's political turmoil and military conflict in north Africa have fuelled a sharp rise in the number of people attempting to reach Europe by sea, with up to 30,000 migrants believed to have made the journey across the Mediterranean over the past four months. Large numbers have died en route; last month more than 800 migrants of different nationalities who left on boats from Libya never made it to European shores and are presumed dead.

"Every morning we would wake up and find more bodies, which we would leave for 24 hours and then throw overboard. By the final days, we didn't know ourselves … everyone was either praying, or dying."

Underlining the dangers, on Sunday more than 400 migrants were involved in a dramatic rescue when their boat hit rocks on Lampedusa.

The pope, meanwhile, in an address to more than 300,000 worshippers, called on Italians to welcome immigrants fleeing to their shores.

The Guardian's investigation into the case of the boat of 72 migrants which set sail from Tripoli on 25 March established that it carried 47 Ethiopians, seven Nigerians, seven Eritreans, six Ghanaians and five Sudanese migrants. Twenty were women and two were small children, one of whom was just one year old. The boat's Ghanaian captain was aiming for the Italian island of Lampedusa, 180 miles north-west of the Libyan capital, but after 18 hours at sea the small vessel began running into trouble and losing fuel.

Using witness testimony from survivors and other individuals who were in contact with the passengers during its doomed voyage, the Guardian has pieced together what happened next. The account paints a harrowing picture of a group of desperate migrants condemned to death by a combination of bad luck, bureaucracy and the apparent indifference of European military forces who had the opportunity to attempt a rescue.

The migrants used the boat's satellite phone to call Zerai in Rome, who in turn contacted the Italian coastguard. The boat's location was narrowed down to about 60 miles off Tripoli, and coastguard officials assured Zerai that the alarm had been raised and all relevant authorities had been alerted to the situation.

Soon a military helicopter marked with the word "army" appeared above the boat. The pilots, who were wearing military uniforms, lowered bottles of water and packets of biscuits and gestured to passengers that they should hold their position until a rescue boat came to help. The helicopter flew off, but no rescue boat arrived.

No country has yet admitted sending the helicopter that made contact with the migrants. A spokesman for the Italian coastguard said: "We advised Malta that the vessel was heading towards their search and rescue zone, and we issued an alert telling vessels to look out for the boat, obliging them to attempt a rescue." The Maltese authorities denied they had had any involvement with the boat.

After several hours of waiting, it became apparent to those on board that help was not on the way. The vessel had only 20 litres of fuel left, but the captain told passengers that Lampedusa was close enough for him to make it there unaided. It was a fatal mistake. By 27 March, the boat had lost its way, run out of fuel and was drifting with the currents.

The only known photo of the ‘left-to-die’ boat

"We'd finished the oil, we'd finished the food and water, we'd finished everything," said Kurke, a 24-year-old migrant who was fleeing ethnic conflict in his homeland, the Oromia region of Ethiopia. "We were drifting in the sea, and the weather was very dangerous." At some point on 29 or 30 March the boat was carried near to an aircraft carrier – so close that it would have been impossible to be missed. According to survivors, two jets took off from the ship and flew low over the boat while the migrants stood on deck holding the two starving babies aloft. But from that point on, no help was forthcoming. Unable to manoeuvre any closer to the aircraft carrier, the migrants' boat drifted away. Shorn of supplies, fuel or means of contacting the outside world, they began succumbing one by one to thirst and starvation.

The Guardian has made extensive inquiries to ascertain the identity of the aircraft carrier, and has concluded that it is likely to have been the French ship Charles de Gaulle, which was operating in the Mediterranean on those dates.

French naval authorities initially denied the carrier was in the region at that time. After being shown news reports which indicated this was untrue, a spokesperson declined to comment.

A spokesman for Nato, which is co-ordinating military action in Libya, said it had not logged any distress signals from the boat and had no records of the incident. "Nato units are fully aware of their responsibilities with regard to the international maritime law regarding safety of life at sea," said an official. "Nato ships will answer all distress calls at sea and always provide help when necessary. Saving lives is a priority for any Nato ships."

For most of the migrants, the failure of the ship to mount any rescue attempt proved fatal. Over the next 10 days, almost everyone on board died. "We saved one bottle of water from the helicopter for the two babies, and kept feeding them even after their parents had passed," said Kurke, who survived by drinking his own urine and eating two tubes of toothpaste. "But after two days, the babies passed too, because they were so small."

On 10 April, the boat washed up on a beach near the Libyan town of Zlitan near Misrata. Of the 72 migrants who had embarked at Tripoli, only 11 were still alive, and one of those died almost immediately on reaching land. Another survivor died shortly afterwards in prison, after Gaddafi's forces arrested the migrants and detained them for four days.

Despite the trauma of their last attempt, the migrants – who are hiding out in the house of an Ethiopian in the Libyan capital – are willing to tackle the Mediterranean again if it means reaching Europe and gaining asylum.

"These are people living an unimaginable existence, fleeing political, religious and ethnic persecution," said Zerai. "We must have justice for them, for those that died alongside them, and for the families who have lost their loved ones."

Additional reporting by John Hooper and Tom Kington in Rome, and Kim Willsher in Paris

Migrants left to die after catalogue of failures, says report into boat tragedy

Council of Europe investigator says deaths of migrants adrift in Mediterranean exposes double standards in valuing human life

28th March 2012 - read the full story here

A catalogue of failures by Nato warships and European coastguards led to the deaths of dozens of migrants left adrift at sea, according to a damning official report into the fate of a refugee boat in the Mediterranean whose distress calls went unanswered for days.

A nine-month investigation by the Council of Europe – the continent's 47-nation human rights watchdog, which oversees the European court of human rights – has unearthed human and institutional failings that condemned the boat's occupants to their fate.

Errors by military and commercial vessels sailing nearby, plus ambiguity in the coastguards' distress calls and confusion about which authorities were responsible for mounting a rescue, were compounded by a long-term lack of planning by the UN, Nato and European nations over the inevitable increase in refugees fleeing north Africa during the international intervention in Libya.

The Guardian first exposed the tale of the "left-to-die" migrant vessel in May last year, after gathering testimony from the voyage's few survivors. Having set sail from Tripoli in the dead of night, the dinghy – which was packed with 72 African migrants attempting to reach Europe – ran into trouble and was left floating with the currents for two weeks before being washed back up on to Libyan shores. Despite emergency calls being issued and the boat being located and identified by European coastguard officials, no rescue was ever attempted. All but nine of those on board died from thirst and starvation or in storms, including two babies.

The report's author, Tineke Strik – echoing the words of Mevlüt Çavusoglu, president of the Council of Europe's parliamentary assembly at the time of the incident – described the tragedy as "a dark day for Europe", and told the Guardian it exposed the continent's double standards in valuing human life.

"We can talk as much as we want about human rights and the importance of complying with international obligations, but if at the same time we just leave people to die – perhaps because we don't know their identity or because they come from Africa – it exposes how meaningless those words are," said Strik, a Dutch member of the council's committee on migration, refugees and displaced persons, and the special rapporteur charged with investigating the case…

Day by Day: How a migrant boat was left adrift on the Mediterranean

They were told they would reach Lampedusa within 18 hours. It was 15 days before the survivors touched land again

28th March 2012 - read the full story here

In the early hours of Saturday, 26 March last year, 72 men, women and children made their way down to a small inflatable dinghy on the shores of Tripoli under the cover of darkness and set sail for what they hoped would be a new life in Europe.

People smugglers were doing brisk business on the back of the chaos and violence of Libya's revolutionary uprising and their work enjoyed the explicit support of Colonel Gaddafi who, as Nato airstrikes began pummelling his country, threatened to unleash an "unprecedented wave of illegal immigration" on to Europe's southern borders.

Those that lived to tell the tale remember that Libyan soldiers accompanied their group down to the boat. On arrival, their basic provisions were removed by the smugglers in an effort to maximise space so that even more migrants could be crammed on board.

"It was completely overcrowded," recalls Bilal Idris, one of only nine survivors from the voyage. "Everyone was sitting on everybody else. I had someone sitting on top of me, and this person had someone sitting on top of him. They don't really care how many people can fit into the boat; all they want is to get the money from each person."

Fifty men, 20 women and two small babies formed the cargo that night. They had been told they would reach the Italian island of Lampedusa within 18 hours. In fact, it would be 15 days before the boat touched land again, with barely anyone on board left alive. Through eyewitness testimony and official communications obtained by the Guardian, the Council of Europe and other journalists who have investigated the case, much of what happened in between can now be revealed…

Migrant boat disaster: those responsible 'could face legal action'

Council of Europe investigator issues warning to those who ignored boat full of African refugees adrift in the Mediterranean

29th March 2012 - read the full story here

The European rapporteur charged with investigating the case of 63 African migrants who were "left to die" in the Mediterranean last year has warned those responsible could end up in court.

On Wednesday, the Guardian revealed the findings of a damning official report into the fateful voyage, which saw the sub-Saharan refugees drifting in the sea for two weeks while dying of thirst and starvation, even though their boat had been located by European authorities and emergency distress calls had been issued to all other ships in the area.

The report blamed a collective set of "human, institutional and legal" failures for the inaction, labelling it a "dark day for Europe" and concluding that large loss of life could have been avoided if the various agencies in the area – Nato, its warships, the Italian coastguard and individual European states – had fulfilled their basic obligations…

Survivor of migrant boat tragedy arrested in Netherlands

Abu Kurke Kebato, who was one of just nine people to survive two weeks adrift in Mediterranean, set to be deported to Italy

29th March 2012 - read the full story here

One of the few survivors from a migrant boat tragedy that claimed 63 lives in the Mediterranean has been arrested by immigration police in the Netherlands and is set to be deported from the country.

The detention of Abu Kurke Kebato, a 23-year-old Ethiopian, came just hours after the European body charged with investigating the incident called on EU member states to look kindly on asylum claims from those who survived the tragedy.

Their dinghy was left drifting for two weeks in the sea despite European authorities pinpointing the location of the vessel and distress calls being sent out repeatedly to nearby ships.

Abu Kurke was among nine people who made it back to land alive from an initial group of 72 that set off from Tripoli in an effort to reach Europe in March last year. The boat was eventually washed back on to Libyan shores. Amazingly he went on to launch another — this time successful — voyage across the sea soon after the tragedy, arriving in Italy before making his way to the Netherlands where he attempted to settle with his wife.

On Thursday morning police acted on an expulsion order and removed the couple from an asylum centre in the Dutch town of Baexem. Under the "Dublin Convention" European states are permitted in some circumstances to deport irregular migrants back to their port of landing, which in this case would be Italy. Abu Kurke's lawyer, Marq Wijngaarden, said he would be lodging appeals with the Dutch supreme court…

Migrant boat disaster: Spain challenges Nato over distress call claim

Spanish government says existence of message must be proved as pressure mounts on Nato over fateful voyage

29th March 2012 - read the full story here

Pressure is mounting on Nato to respond to a series of unanswered questions concerning the tragedy of the migrant boat, with European politicians repeating their demands for a further inquiry and human rights lawyers announcing the launch of legal action against those responsible for the "avoidable" loss of life…

Despite initially insisting that Nato "had not logged any distress signals from the boat and had no records of the incident", this week the organisation admitted it had received a fax giving details of the troubled boat and its precise location.

A spokesman claimed the information "was forwarded to Nato taskforce units under its operational control", which would have included the Méndez Núñez, a Spanish frigate equipped with helicopters that was positioned only a few miles from the migrants at the time.

On Thursday the Spanish ministry of defence denied that any such communication was received. "The frigate did not receive any notification from the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre of Rome or from the Nato command in Naples," spokesman Miguel Morer told the Guardian…

Migrant boat tragedy: UK crew may have seen doomed vessel

Latest report raises possibility British helicopter was aware of people adrift for two weeks without food or water

11th April 2012 - read the full story here

A damning new report into the death of dozens of African migrants who were left drifting in the Mediterranean last year has concluded that Nato contributed to the 63 deaths, and raises the possibility of British military forces being connected with the tragedy.

The 90-page study by experts at Goldsmiths, University of London, employed cutting-edge forensic oceanography technology to determine the exact movements of the doomed migrant vessel, which was left drifting for two weeks in one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, despite European and Nato officials having been aware of the boat's plight and location.

Almost everyone on board, including two babies, eventually died of thirst and starvation.

The report reveals that the survivors' description of a military helicopter that twice hovered over and communicated with their boat, but flew off without attempting a rescue, corresponds almost exactly to the British army's Westland Lynx helicopter. Units of Lynxes are known to have been operating in the Mediterranean during the Libyan conflict, but the Ministry of Defence has denied any were present at the time of the incident and insists there is no record of any of their forces encountering the dinghy.

It also quotes survivor testimony suggesting that a naval vessel that came into direct contact with the migrants, which also ignored their cries for help, could have been French.

The latest revelations will increase the pressure on Nato to release classified imagery and data that could help identify the units responsible for failing to mount a rescue operation. The question of which units ignored the migrants gained significance on Wednesday after French human rights lawyers formally announced the start of legal action against those deemed culpable of the deaths…

Council of Europe demands policy overhaul to stop migrant boat deaths

Call follows 2011 incident in which dozens of refugees were left to die in Mediterranean despite desperate appeals for help

24th April 2012 - read the full story here

Europe's leading human rights watchdog has called for an overhaul of policy on migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean following an incident last year in which dozens of Africans were left to die in a rubber dinghy despite their desperate appeals for help.

In a significant about-turn, Nato expressed "deep regret" for any role it may have played in the tragedy – but the alliance was swiftly accused by Liberal Democrat MP Mike Hancock of a cover-up over the deaths. Hancock said he plans to raise the issue in parliament next week.

On Tuesday a debate by the 47-nation Council of Europe on the fate of 72 migrants who set sail from Tripoli to Italy at the height of the Libyan war, only to run into trouble several hours later and end up drifting with the currents, united parliamentarians from across the political spectrum in anger at the huge and unnecessary loss of life.

The story of the doomed vessel, first revealed by the Guardian in May 2011, has gathered pace since it emerged that European authorities were aware of both the exact location and critical plight of the migrants, 63 of whom eventually perished of thirst and hunger. Despite the boat coming into contact with a series of military units over the subsequent two weeks, no rescue was ever attempted.

In an effort to prevent a similar tragedy from happening again, the Council of Europe has now endorsed a thorough review of existing protocols regarding migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean. The council's recommendations include better clarification on the demarcation of search and rescue obligations between states, improved communication between national coastguards and military vessels, an end to any ambiguity over what constitutes a distress call, and more long-term planning to anticipate higher migrant flows at times of military conflict – all factors that helped condemn the "left to die" vessel in late March and early April last year…