Egypt 2011: ‘The World Turned Upside Down’

A selection of news, comment and analysis from Jack Shenker’s award-winning Guardian coverage of Egypt’s revolutionary uprising

-Published in the Guardian and Observer

-Egypt / 2011

-Winner of the Amnesty International Gaby Rado award, a Webby award, and shortlisted for the Kurt Schork and Anna Lindh prizes

“My notebooks are as raw as my memories. Two of the spiral- bound ones are twisted, their spines dislocated from the pages; when you pick them up, they spill sheets carelessly upon the table. The handwriting is hurried, messy – words have been snatched hastily to the paper amid drumbeats and shouts and gas and flight, and they’ve brought bits of that universe with them: grubby stains, smears of rock dust, strange ink. Pens were dropped all the time in the struggle and new ones borrowed, so sentences appear in different colours and some of them are splotched by teardrops. Many pages are torn, and a few are missing. It’s as if the notebooks refused to stand separate, refused to seal themselves off into tidy organs of record while revolution raged around them.

During those eighteen days in Tahrir, I filled five journals with thoughts, quotes, yelled names and scribbled phone numbers. With most shops closed, stationery supplies were hard to come by so I had to make do with whatever was available. The last notebook is actually an address book grabbed from an empty hotel gift shop, a preposterous- looking substitute with tan stitching across the cover and gold leaf daubed around the edges. Because it was designed for Arabic script and I write my notes in English, I flipped the address book over before using it – inadvertently upending a map of the globe printed on the first page. I don’t remember when, but at some point during the uprising – maybe in a quiet corner of a field hospital as I waited to speak to a harried, blood- spattered volunteer doctor, or maybe crouched and panting behind a makeshift barricade, gulping down water offered by a stranger – I wrote in big letters across that map: ‘The World Turned Upside- Down’. The words are underlined with such intensity that the pen’s nib has punctured the paper.”

- Excerpt from ‘The Egyptians: A Radical Story’

In January 2011, Jack was based in Cairo as Egypt correspondent for the Guardian newspaper when the country - ruled for three decades by the same western-backed dictator - was convulsed by revolution. Across the 18 day anti-Mubarak uprising that eventually toppled Egypt’s ageing president, and the months of turmoil that followed as military generals, revolutionary forces and competing political factions battled for supremacy, he reported from the frontline of the struggle in Cairo and beyond.

What follows is a small selection of excerpts from and links to those stories, many of which were produced with colleagues. For the full archive of articles from this period, please visit the Guardian website. Jack’s book on Egypt - exploring the revolution and counter-revolution from below - was published by Allen Lane and Penguin in 2016; for more information on it, click here.

Egypt's frustrated young wait for their lives to begin, and dream of revolution

January 23rd (two days before the start of the revolution) - full story here

In Cairo, as in places all over the country, all eyes are fixed on the drama that is unfolding in Tunisia. Jack Shenker travelled across Egypt and heard people increasingly asking: could it happen here, and if so, when?

News of the latest act of self-immolation in Egypt reached Waleed Shamad while he was sitting in the bourse, a dense warren of outdoor shisha cafes tucked away in the back alleys surrounding Cairo's old stock exchange.

An unemployed man had set himself alight in the middle of a busy street – the 12th such incident last week. According to a TV newsreader, the man, 35, had moved to the capital in the hope of finding work and saving enough to buy a home and get married, but lack of job opportunities had driven him to despair. "That could be a description of any of us," said Waleed, pulling his scarf tighter against the cold. "These human blazes are coming so fast, it's hard to keep track."

Cairo is a city built for sunny days and balmy nights; come winter the wind can lash with a ferocious bite. But that has not stopped Shamad and his friends gathering for their late-evening tea on the pavement to talk through the day's gossip: the Friday sermons devoted to Islam's disapproval of suicide, new government restrictions on buying bottled petrol, and, of course, all the latest from Tunis – where developments have kept the group glued to al-Jazeera TV for days.

"We couldn't believe our eyes," grinned Shamad, recalling the sight of Tunisia's ousted despot, Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, fleeing a land he had ruled for 23 years. "I'm so proud of the Tunisian people. When you see a friend or brother succeeding in some great struggle, it gives you hope, hope for yourself and hope for your country…"

Bloody and bruised: the journalist caught in Egypt unrest

January 25th (first night of the revolution) - full story here, and original audio here

The Guardian's correspondent in Cairo tells of his beating and arrest at the hands of the security forces

In the streets around Abdel Munim Riyad square the atmosphere had changed. The air which had held a carnival-like vibe was now thick with teargas. Thousands of people were running out of nearby Tahrir Square and towards me. Several hundred regrouped; a few dozen protesters set about attacking an abandoned police truck, eventually tipping it over and setting it ablaze. Through the smoke, lines of riot police could be seen charging towards us from the south.

Along with nearby protesters I fled down the street before stopping at what appeared to be a safe distance. A few ordinarily dressed young men were running in my direction. Two came towards me and threw out punches, sending me to the ground. I was hauled back up by the scruff of the neck and dragged towards the advancing police lines.

My captors were burly and wore leather jackets – up close I could see they were amin dowla, plainclothes officers from Egypt's notorious state security service. All attempts I made to tell them in Arabic and English that I was an international journalist were met with more punches and slaps; around me I could make out other isolated protesters receiving the same brutal treatment and choking from the teargas.

We were hustled towards a security office on the edge of the square. As I approached the doorway of the building other plainclothes security officers milling around took flying kicks and punches at me, pushing me to the floor on several occasions only to drag me back up and hit me again. I spotted a high-ranking uniformed officer, and shouted at him that I was a British journalist. He responded by walking over and punching me twice. "Fuck you and fuck Britain," he yelled in Arabic.

One by one we were thrown through the doorway, where a gauntlet of officers with sticks and clubs awaited us. We queued up to run through the blows and into a dank, narrow corridor where we were pushed up against the wall. Our mobiles and wallets were removed. Officers stalked up and down, barking at us to keep staring at the wall. Terrified of incurring more beatings, most of my fellow detainees – almost exclusively young men in their 20s and 30s, some still clutching dishevelled Egyptian flags from the protest – remained silent, though some muttered Qur'anic verses and others were shaking with sobs.

We were ordered to sit down. Later a senior officer began dragging people to their feet again, sending them back out through the gauntlet and into the night, where we were immediately jumped on by more police officers – this time with riot shields – and shepherded into a waiting green truck belonging to Egypt's central security forces. A policeman pushed my head against the doorframe as I entered.

Inside dozens were already crammed in and crouching in the darkness. Some had heard the officers count us as we boarded; our number stood at 44, all packed into a space barely any bigger than the back of a Transit van. A heavy metal door swung shut behind us.

As the truck began to move, brief flashes of orange streetlight streamed through the thick metal grates on each side. With no windows, it was our only source of illumination. Each glimmer revealed bruised and bloodied faces; sandwiched in so tightly the temperature soared, and people fainted. Fragments of conversation drifted through the truck.

"The police attacked us to get us out of the square; they didn't care who you were, they just attacked everybody," a lawyer standing next to me, Ahmed Mamdouh, said breathlessly. "They … hit our heads and hurt some people. There are some people bleeding, we don't know where they're taking us. I want to send a message to my wife; I'm not afraid but she will be so scared, this is my first protest and she told me not to come here today."

Despite the conditions the protesters held together; those who collapsed were helped to their feet, messages of support were whispered and then yelled from one end of our metallic jail to another, and the few mobiles that had been hidden from police were passed around so that loved ones could be called.

"As I was being dragged in, a police general said to me: 'Do you think you can change the world? You can't! Do you think you are a hero? You are not'," confided Mamdouh.

"What you see here – this brutality and torture – this is why we were protesting today," added another voice close by in the gloom.

Speculation was rife about where we were heading. The truck veered wildly round corners, sending us flying to one side, and regularly came to an emergency stop, throwing everyone forwards. "They treat us like we're not Egyptians, like we are their enemy, just because we are fighting for jobs," said Mamdouh. I asked him what it felt like to be considered an enemy by your own government. "I feel like they are my enemies too," he replied.

At several points the truck roared to a stop and the single door opened, revealing armed policemen on the other side. They called out the name of one of the protesters, "Nour", the son of Ayman Nour, a prominent political dissident who challenged Hosni Mubarak for the presidency in 2005 and was thrown in jail for his troubles.

Nour became a cause celebre among international politicians and pressure groups; since his release from prison security forces have tried to avoid attacking him or his family directly, conscious of the negative publicity that would inevitably follow.

His son, a respected political activist in his own right, had been caught in the police sweep and was in the back of the truck with us – now the policemen were demanding he come forward, as they had orders for his release.

"No, I'm staying," said Nour simply, over and over again and to applause from the rest of the inmates. I made my way through the throng and asked him why he wasn't taking the chance to get out. "Because either I leave with everyone else or I stay with everyone else; it would be cowardice to do anything else," he responded. "That's just the way I was raised."

After several meandering circles which seemed to take us out further and further into the desert fringes of the city, the truck finally came to a halt. We had been trapped inside for so long that the heat was unbearable; more people had fainted, and one man had collapsed on the floor, struggling for breath.

By the light of the few mobile phones, protesters tore his shirt open and tried to steady his breathing; one demonstrator had medical experience and warned that the man was entering a diabetic coma. A huge cry went up in the truck as protesters thumped the sides and bellowed through the grates: "Help, a man is dying." There was no response.

After some time a commotion could be heard outside; fighting appeared to be breaking out between police and others, whom we couldn't make out.

At one point the truck began to rock alarmingly from side to side while someone began banging the metal exterior, sending out huge metallic clangs. We could make out that a struggle was taking place over the opening of the door; none of the protesters had any idea what lay on the other side, but all resolved to charge at it when the door swung open. Eventually it did, to reveal a police officer who began to grab inmates and haul them out, beating them as they went. A cry went up and we surged forward, sending the policeman flying; the diabetic man was then carried out carefully before the rest of us spilled on to the streets.

Later it emerged that we had won our freedom through the efforts of Nour's parents, Ayman and his former wife Gamila Ismail. The father, who was also on the demonstration, had got wind of his son's arrest and apparently followed his captors and fought with officers for our release. Shorn of money and phones and stranded several miles into the desert, the protesters began a long trudge back towards Cairo, hailing down cars on the way.

The diabetic patient was swiftly put in a vehicle and taken to hospital; I have been unable to find out his condition.

Egypt's day of fury: Cairo in flames as cities become battlegrounds

January 28th (fourth day - and pivotal turning point - of the revolution) - full story here

Hosni Mubarak regime left reeling as thousands defy curfew; Police fire baton round volleys into crowds unwilling to retreat

When Mohamed ElBaradei arrived in Midan Giza, a traffic-snarled interchange on the west bank of the Nile, for Friday prayers, he saw a graphic illustration of Egypt under President Hosni Mubarak: neat rows of police and plainclothes security officers lining the streets to maintain calm.

By the time he left the central Cairo square an hour or so later it was in flames, doused with teargas and water cannon and with rocks flying through the air – a glimpse of what an Egypt sick of Mubarak had become.

By the evening the first military vehicles of the Egyptian army would be out on the capital's streets, swathed in clouds of gas and smoke from burning tyres and buildings, and ElBaradei, according to reports, would be under house arrest.

It was billed on the internet by those organising the protests as a day of "fury and freedom" – a historic moment for an Egypt that has seen anger and fury aplenty. Whether it delivered freedom remains an open question. The presidential hopeful had come to the Al Istiqama mosque to pray; before he left his home he told the Guardian it would be a day of confrontation with a regime on its last legs. He had barely finished worship when the regime struck back, firing bombs and gas into the crowd and sending riot police charging with batons. ElBaradei was whisked away by supporters; thousands of others were forced to scatter into back alleys, choking and chanting amid the smoke. Egypt's day of fury had begun…

'Mubarak must fall' – all across Cairo the protesters' message is the same

30th January (fifth day of the revolution) - full story here

Sacrificing government ministers is not enough: for the people to be satisfied, the president must be deposed

As evening fell across central Cairo's Tahrir Square, a black cloud of smoke welled in the distance from close to the interior ministry. The sound of shots rang out. First one. Then bursts. Then more shots: live rounds, rubber baton rounds, and gas.

If it was intended to frighten the crowds who had milled around the square all day, it seemed by early evening to have failed. "I've just been hit. They're shooting live ammunition at us. I can see blood on the floor," said veteran Egyptian activist Ahmed Salah, who had been hit by pellets and spoke to the Observer on the phone. But he remained undaunted: "If we persist, then Hosni Mubarak will surely leave."

Yesterday, just as it has been for the past five days, Tahrir Square was the new centre of the surging revolution that has seized the Arab world.

Far from being cowed or placated, the thousands of protesters were instead determined to hold their ground. Determined – as they have been for days – to insist on the removal of Mubarak, Egypt's president for three decades. In Cairo it was scrawled across walls and written over statues: "Mubarak must fall."

As Egypt erupted in a fifth day of dissent and popular anger, the square nursed its wounds of revolution – as did the people, bandaged and bruised, who turned up to fill it again…

Egypt protesters react angrily to Mubarak's televised address

1st February (eighth day of the revolution) - full story here

'How dare he talk to us like children?' say demonstrators. 'If he's here until September then so are we'

The crowd had rigged up a huge screen to show al-Jazeera. Mubarak's speech was broadcast live. As he announced that he would not be standing for another term, the rally exploded in anger.

The screen was pelted with bottles and the cry "Irhal, irhal" went up repeatedly: "Leave, leave". It was taken up by the hundred thousand people who thronged Tahrir Square. At one point demonstrators held up their shoes to the screen – an insulting gesture in Arab culture.

None of them were appeased by Mubarak's announcement. If anything, they were emboldened to step up their protests and to push their demands further. Many were saying that not only must Mubarak leave immediately but that the whole of his National Democratic party regime had to go and should be put on trial.

"If he's here until September then so are we," said Amr Gharbeia, an activist who is camping out in the square…

Egypt's revolution turns ugly as Mubarak fights back

2nd February (ninth day of the revolution) - full story here

Extraordinary scenes in central Cairo; Violent battles in cities across the country; Foreign journalists deliberately targeted

Egypt's pro-democracy revolution descended into violence and bloodshed overnight as President Hosni Mubarak's regime launched a co-ordinated bid to wrest back control of city streets, crush the popular uprising, and reassert its authority.

Bursts of heavy gunfire rained into Tahir square just before dawn today and there were reports that three more people had been killed. Protest organiser Mustafa el-Naggar said he saw the bodies of three dead protesters being carried toward an ambulance, while another witness spoke of 15 people being wounded.

Clashes had continued into the early hours even though the pro-Mubarak supporters had been pushed back to the edge of the square and explosions – possibly from gas canisters – echoed around the area.

There were extraordinary scenes in the centre of Cairo as anti-government demonstrators fought running battles with organised cohorts of Mubarak supporters, exchanging blows with iron bars, sticks and rocks.

At one point pro-Mubarak forces rode camels and horses into central Tahrir Square, scattering opponents…

Mubarak supporters fight to take over Egypt's Tahrir Square

2nd February - full story here

Claims that plainclothes police hidden in ranks as battles take place in the symbolic epicentre of the revolution

The men came with baseball bats and pieces of broken window frame, machetes and even a homemade spear. Forming a line, the small group of plainclothes policemen blocked one of the broad boulevards leading into Tahrir Square, the symbolic epicentre of the Egyptian revolution.

The police had been driven from the streets they are so used to controlling last Friday and now they had come to reclaim what they regarded as rightfully theirs. As they gathered on Qasr el-Aini, they prepared themselves for confrontation with the protesters who had humiliated them and their president.

Yesterday was not a day of revolution. It was the beginning of a vicious counter-revolution in support of Hosni Mubarak's regime, one that seemed set fair to confirm all his critics' fears.

The day after hundreds of thousands of anti-Mubarak demonstrators had filled Tahrir Square to demand his ousting, the supporters of Egypt's president of 30 years had come to reclaim it with violence.

The men came by car and on foot, some even on camel and horseback, arriving as Mubarak's regime – in a dramatic U-turn – defiantly rejected international calls for an orderly transition of power…

The Tahrir Square medic

6th February (thirteenth day of the revolution) - full story here

Dina Omar is a 30-year-old Egyptian cardiologist living in Beirut; when news broke of Egypt's anti-Mubarak uprising last month she flew back to Cairo and has been working at a frontline medical station in Tahrir Square since.

“On Sunday I persuaded my family that we should all donate blood to help those injured in Friday's fighting. While me and my sister were waiting in line I suggested to her that we go and take a look first-hand at what was happening in Tahrir. Soon after we arrived a young boy, probably about 13 years old, came up to me and asked whether I was a doctor. When I said yes, he told me his brother had been killed on Friday. He said it with no grief or tears – he was calm and polite, as if he just needed to inform someone. I asked him if he knew of any medical centre in the square that I could offer supplies to. He took me to a nearby mosque where the medics told me they were in need of a cardiologist…

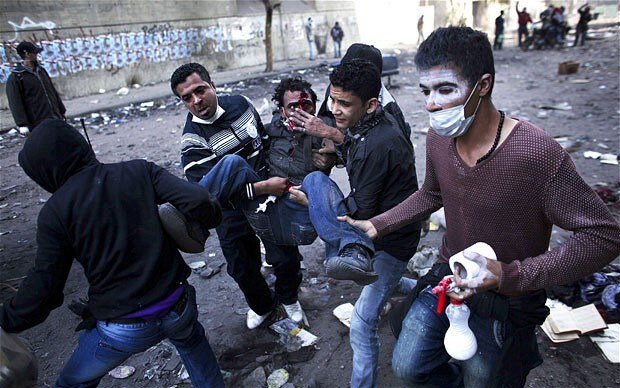

Conditions were so hard; it was dark, there were rocks and Molotov cocktails being thrown towards us, and at any one time we had more than 30 people desperate for treatment. At one point a bus of baltagiyya (thugs) drove right up to us and we had to flee and scatter, each carrying our patients.

But from a medical point of view we did amazingly; even in the middle of a war zone we managed to keep most of the needles sterile, and when we couldn't sterilise them we didn't use them – it is better to bathe and clean a wound and leave it unstitched than it is for them to contract Aids or hepatitis.

I treated over 200 patients that night, two of whom died in my lap. One 23-year-old was brought to me seemingly unconscious, with his head wrapped in bandages; we tried CPR for several minutes but it was clear we were too late. It was only when someone else ran up to us with a towel wrapped around a complete human brain that I realised what had happened – we turned the patient over and saw that the whole back of his head was missing. And of course there was no time to shed a tear. ‘Yalla (let's go),’ I said, ‘next patient…’”

Egypt's rich may do business as usual, but their children are protesting

7th February (fourteenth day of the revolution) - full story here

In New Cairo – a satellite city to the east of the capital – life, on the surface at least, seems to have barely changed

The grass is cut as finely as ever on the Katameya Heights golf course, and cigars are still being smoked discreetly in the clubhouse. Glancing around the lobby, one could be forgiven for thinking nothing had ever disturbed this gated citadel of Cairo luxury; indeed the ladies' day Valentine's tournament is to go ahead as scheduled.

There is just one tactful nod to the turmoil that has shaken Egypt to its foundations in the past fortnight: a short letter to members, pinned to a noticeboard by the fountain. "Welcome back – we hope you and your families are all safe," it reads. "The 18-hole operating hours are as follows."

Yet as Egypt's pro-change uprising enters its third week, a return to normality in places such as New Cairo is exactly what those camped out 15 miles away in Tahrir Square desperately want to avoid…

Egypt's day of rumour and expectation ends in anger and confusion

10th February (seventeenth day of the revolution) - full story here

Vast crowds in Tahrir Square expected a victory party – but it was not to be

Rain is rare in Cairo, thunder even more so. Tahrir Square experienced both, and those on the ground took it as a seal of approval for their revolt. As one demonstrator said, looking skyward: "You don't bring down a 30-year dictatorship without a bit of hand-clapping from the gods." But the turbulent weather turned out to be an omen for something else – another night of bitter disappointment and confusion.

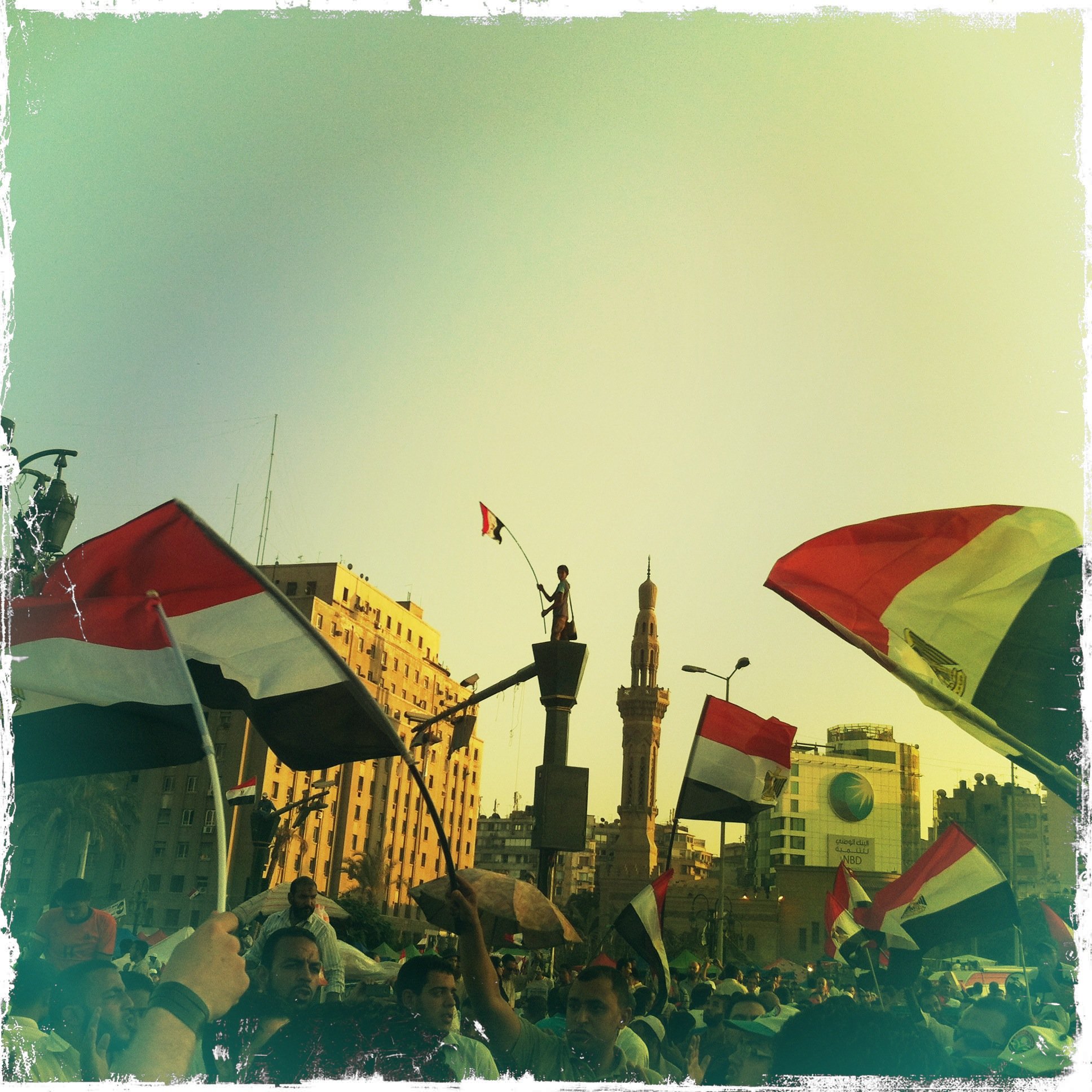

Tahrir has been no stranger to mood swings over the past 17 days, but none have been as devastating as this. As darkness fell tens of thousands streamed in to join an ocean of songs, drums and flags; with Mubarak's resignation expected imminently, it seemed as if the Egyptian capital was gearing up for the biggest street party the Arab world has ever seen.

By half past 10, when the president finally shuffled on to the stage, a deathly hush swept the square. Everywhere groups huddled round transistor radios, straining to hear his words. Some thrust camera phones high into the air. "I want to capture the very moment of his departure so I can show my future children," whispered one. That moment never came.

With the crowd desperate to hear what he had to say, Mubarak's staid nationalistic rhetoric squeaked out of a hundred tiny speakers into near silence. There was no interruption when he called for national unity, and only the faintest of tuts when he tried to invoke the memory of those who had died in Egypt's anti-government uprising, deaths many in the square attribute to his forces.

But then he told the listening protesters that he too was a young man once, and could understand their concerns. In an instant, Tahrir shook with fury.

Many took off their shoes and waved them in the air (below). Pockets of protesters launched different chants: "Down, Down, Hosni Mubarak" and "We're not going until he goes". Soon they coalesced, and the square spoke as one with a single word. 'Irhal' ('Leave'), it cried…

Hosni Mubarak resigns – and Egypt celebrates a new dawn

11th February (eighteenth day of the revolution) - full story here

President surrenders power to army and flies out of Cairo; Egypt rejoices as 18 days of mass protest end in revolution; Military pledges not to get in way of 'legitimate' government

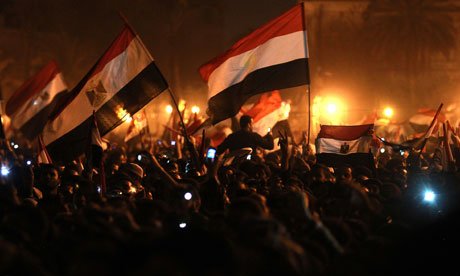

When it finally came, the end was swift. After 18 days of mass protest, it took just over 30 seconds for Egypt's vice-president, Omar Suleiman, to announce that President Hosni Mubarak was standing down and handing power to the military.

"In the name of Allah the most gracious the most merciful," Suleiman read. "My fellow citizens, in the difficult circumstances our country is experiencing, President Muhammad Hosni Mubarak has decided to give up the office of the president of the republic and instructed the supreme council of the armed forces to manage the affairs of the country. May God guide our steps."

Moments later a deafening roar swept central Cairo. Protesters fell to their knees and prayed, wept and chanted. Hundreds of thousands of people packed into Tahrir Square, the centre of the demonstrations, waving flags, holding up hastily written signs declaring victory, and embracing soldiers.

"We have brought down the regime, we have brought down the regime," chanted the crowd…

In Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the freedom party begins

11th February - full story here

Jubilant Egyptians celebrate Hosni Mubarak's resignation

Cairo, in Arabic, means "victorious". Last night the Egyptian capital lived up to its name. After 30 years of dictatorship and 18 days of struggle, the end, when it came, took most people by surprise. The crowds that had been steadily gathering outside the presidential palace all afternoon were swaying with their normal rhythm of quietly controlled passion, pockets of singing here, flags waved there. Word spread an important announcement was expected, but few held out much hope. They had anticipated triumph the night before and seen it snatched from their hands. This time, though, it would be different.

At 6pm, beneath the belle epoque domes of the building from which President Hosni Mubarak had ruled for so long, a cry went out that he was gone. Most of those below have never known another leader, and in an instant the street was convulsed with a wild, directionless surge of energy.

For a few moments it was simply a wall of sound, and Egypt's national colours blurred through the sky from every angle. And then the world came back into focus. "Freedom," roared a jubilant crush of humanity as the party got under way.

Families and friends were separated in the throng, but it didn't matter; hugs and kisses and dances were thrown out indiscriminately. People bounced from one circle of cheering youths to another; some put their national flags on the floor and began to pray; others fainted, quite overcome with the emotion.

"For 18 days we have withstood teargas, rubber bullets, live ammunition, Molotov cocktails, thugs on horseback, the scepticism and fear of our loved ones, and the worst sort of ambivalence from an international community that claims to care about democracy," said Karim Medhat Ennarah, a protester with tears in his eyes. "But we held our ground. We did it.

"My late father was part of a sit-in at the faculty of engineering in Cairo University in 1968 – the first protest seen in Egypt since Nasser took over in 1952," he added. "His generation tell me that they were not as brave as us, but they started something and played their part. Today, we finished the job for them..."

Film short: Egypt, Football and Revolution

7th July - original video here

Produced with Richard Sprenger and Simon Hanna

Winner of a 2012 Webby award

Since the fall of Hosni Mubarak, politics has entered every aspect of Egyptian life - even football. This is most evident in the Cairo derby, a game between arch rivals Al Ahly and Zamalek

How youth-led revolts shook elites around the world

12th August - full story here

Shortlisted for the Anna Lindh award

From Athens to Cairo and Spain to Santiago, old certainties are being challenged after the Arab uprisings and global financial crises

Of all the millions of words expended in the global media on this year's rash of youth-led revolts across the globe, none are more relevant than those penned by Alex Andreou, a Greek-born blogger who now lives in Britain. "You have run out of ideas," he wrote in June, echoing the message of Greek protesters to their country's political and economic elites. "Wherever in the world you are, that statement applies."

Andreou was writing as the occupation of Syntagma Square – Athens's central plaza – was entering its fourth week, and he went on to summarise what had moved Greek demonstrators to take to the streets: a refusal to suffer any further in order to make the rich even richer, a withdrawal of consent and trust from the politicians governing in their name, and finally that simplest and most devastating of censures from one generation to the next. Those in power, he said, were devoid of fresh thinking, and this is why "the protests in Greece affect all of you directly".

When the dust has settled on 2011 perhaps the aspect of it that will prove most striking to historians is that in a period where so many old certainties dissolved, from the stability of dictatorships in the Middle East to the sturdiness of the neoliberal economic framework in Europe, America and beyond, those with their hands on the levers of formal power had so few ideas to offer. From Arab autocrats to eurozone finance ministers, paucity of original thought has prevailed at the top and the prescription has always been more of the same: reheated rhetoric and stencil-cut solutions, all worn lifeless with weary familiarity.

Little wonder then that from Santiago to Sana'a, something else has arisen to fill the void – and that those still rooted in the old models of thinking find themselves lacking the linguistic tools necessary to even describe the phenomenon, never mind understand it…

Tahrir Square crowds vow 'fight to death' for end of military rule

21st November - full story here

Shortlisted for the Kurt Schork award

Egypt's ruling junta has slowly transformed from heroes of uprising to the focus of its wrath

Amid the gloom, the smoke and the deafening chants of thousands around them, the middle-aged couple looked like they had been photoshopped on to the scene. He was wearing a smart jacket, she a dress and a headscarf. They both walked silently forwards across the debris, hand in hand and staring straight ahead. Each was carrying a rock.

The scene was Talaat Harb street, usually one of downtown Cairo's busiest thoroughfares and a shopping mecca for cut-price shoes and clothing, just after darkness fell across the capital on Sunday evening. The store shutters were down and the dying and the injured were propped up against them. Ahead, beyond a wall of teargas, stood the troops of Egypt's once-venerated army, and the new frontline of this country's reawakened revolution…

Tahrir Square protesters killed by live ammunition, say doctors

24th November 2011 - full story here

Shortlisted for the Kurt Schork award

Egypt's ruling generals accused by human rights group after morgue workers in Cairo contradict official claims

Egypt's ruling generals have been accused by a human rights organisation of having blood on their hands after medical workers confirmed that live ammunition had been used against anti-junta demonstrators in Tahrir Square.

According to morgue officials, at least 22 Egyptians have been killed by live bullets since street battles began on Saturday, directly contradicting government statements that security forces have never opened fire on protesters.

One hospital doctor told the Guardian he had personally seen 10 patients struck by live ammunition during the protests that have swept Egypt in the past six days, six of whom did not survive.

"Many of the fatalities were as a result of a single shot to the head," said Hesham Ashraf, of Qasr el-Aini hospital, one of central Cairo's largest medical facilities…